The term Kalamkari is derived from kalam, the Persian word for pen and kari (work) and literally means ‘pen work’. These are traditionally made in a small town called Kalahasti in the Chittoor district in Andhra Pradesh.

Step by Step Making of Kalamkari Painting

Kalamkari is the art of painting cotton fabrics with a kalam, a sharp pointed bamboo stick padded with hair or cotton and tied with a string on one end to regulate the flow of color. The art was exclusive to cotton fabric.

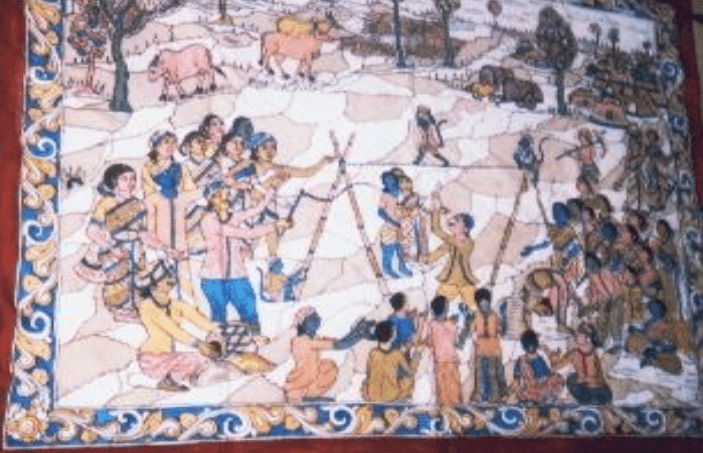

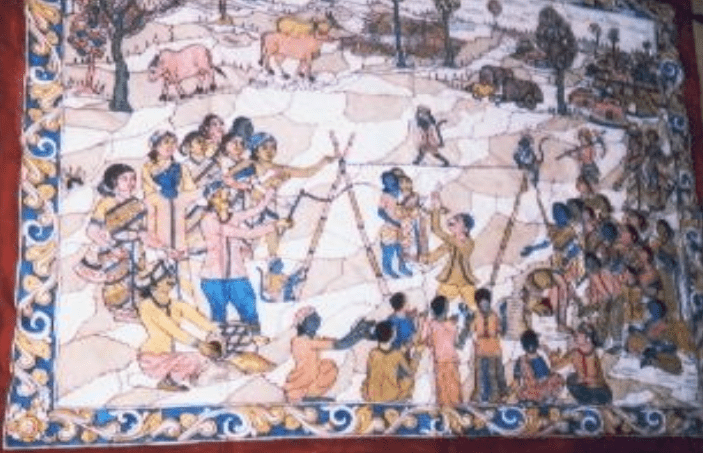

The style practiced in Kalahasti maintains more traditional methods of outlining features and drawing designs using a kalam rather than blocks. The art of Kalamkari comprises hand-drawn, painted and dyed wall cloth, in natural colors. From giant tapestries to small squares, these cloth paintings with their densely packed characters and storyboard narratives have freshness about them.

The themes of Kalamkari fabrics are traditionally chosen from the Puranas or epics. These stories are depicted in the form of a series of horizontal panels with the narrative script running through with more important incidents receiving a larger layout.

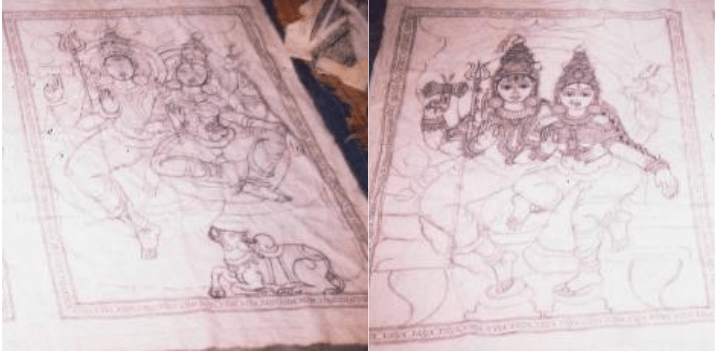

The distinctive temple wall hangings, chariot decorations and canopies of Srikalahasti typically feature Hindu stories, and the images are often identified with text in Telugu, the regional language. Temples were a major inspiration in the Srikalahasti Kalamkari paintings.

The art flourished under the patronage of the temples with their demands for hangings with strong figurative and narrative components. This specialization in figurative work continues till today.

Kalamkari is as much a craft as it is an art. The laborious process involved with each painting takes around 40 days (the designing takes about four days and the entire process of painting takes around 30-35 days) depending on the climatic conditions. Most of the raw materials are gathered from forests and processed by traditional methods.

Background and Interventions

The art of Kalamkari flourished in temple towns along the eastern coast of Andhra Pradesh. With the decline of temples and patronage from royal families the art declined as well. It was in the temple town of Kalahasti near Tirupathi that, during the 1950s, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya discovered the dying art of Kalamkari with the help of Jonnalagadda Laxamaiah and Kalappa.

There were only two artists left who knew the Kalamkari tradition. But there was no one to pass it down to. With the help of Avani Kalappa, Chattopadhyaya started a training school in the village. The present generation of artists and students has recovered the tradition of Kalamkari and are infusing the art with individual styles.

The discovery of a resist-dyed piece of cloth on a silver vase at the ancient site of Harappa confirms that the tradition of Kalamkari is very old. Even the ancient Buddhist

Chaitya Viharas were decorated with Kalamkari cloth. In the 17th century, Kalamkari paintings were exported to Iran, Burma, the Persian Gulf, Maldives and Malacca. The craft gained immense popularity in the 18th century throughout Europe, with the fabric being used as draperies and bedspreads.

The Kalamkari floral and vegetable designs were in great demand, in particular the motif known as the ‘Tree of Life’. These fabrics were made into dresses, skirts and jackets and were also used as large wall hangings.

Today, there are several groups of Kalamkari artisans in Kalahasti. The Srikalahasti Kalamkari Kala Karula Sangham, is one of the co-operatives of Kalamkari artisans, which has worked with the non-government organization Dastkar Andhra and the Crafts Council of India to bring Kalahasti Kalamkari to the forefront.

The former has been instrumental in changing the monochrome red in the wall hangings to a more diverse color palette. New themes such as stories from the Panchatantra were also introduced in addition to the conventional religious depictions.

Producer Communities

The practitioners of Kalamkari are of Hindu castes such as Reddy, Padmasali, Chakali, Mala, Madiga Devanga and Balija. These producer groups mainly reside in and around Srikalahasti, Ilaganuru, Kapugunneru, Kannali, Kuppam, Gundelugumta and Panagalu.

Raw Materials

These raw materials are available in Chittoor (Andhra Pradesh) and in Chennai. In addition to the below mentioned raw materials, the following are also used–rusted iron, tamarind twigs, alum, cow’s milk and cow dung.

Tools Used

The tools used are very simple

Charcoal Pencil

Twigs from nearby tamarind trees are collected and burnt. The fire is frequently prodded to make sure that all the pieces are evenly burnt. When the twigs are half-burnt and blackened, the fire is extinguished with sand. This process is done to cool the twigs. Half-burnt twigs form the charcoal pencil. The charcoal drawing provides the basic layout in the Kalamkari painting.

Kalam or Pen

Two types of pens are used. They are made with bamboo sticks. One is a sharp-tipped one for outline drawing; the other has a broad, round tip and is used for filling in with mordant. The broad-tipped kalamhas a fibrous edge.

Myrobalan Paste

Myrobalan is soaked overnight in water, and then ground on a grinding stone to make a thick paste.

Washing of Cloth and Process for Myrobalan

For painting, the craftsmen use thick unbleached cloth called gadha. First the cloth is washed in running water (in the river close by) so that the starch is removed.

Process

The process involves washing, rinsing, soaking and bleaching the fabric and applying mordants and dyes using natural substances like indigo (blue), madder (red), mango bark (yellow) and palm sugar (black). Painting on the fabric is done with a kalam, charcoal and myrobalan paste.

In a large vessel, a handful of myrobalan paste is mixed with one liter of water and fresh buffalo milk.

The washed cloth is folded loosely to permit easy permeation of myrobalan. The cloth is slowly dipped into the solution. It is then opened up part by part and soaked again and pressed down with the hands. This type of pressing helps greater absorption.

Then the cloth is taken out, wrung and opened out. The wringing helps remove the thicker particles of myrobalan.

The process of opening, folding and twisting the cloth is repeated again, but this time the twisting is done in the opposite direction. The squeezing motion helps to spread the fat content of the buffalo milk. The fat holds the colors on the surface and prevents color from spreading. This effect on the fabric lasts for one month.

Once all the pieces of cloth have been processed, they are spread out to dry in the sunlight.

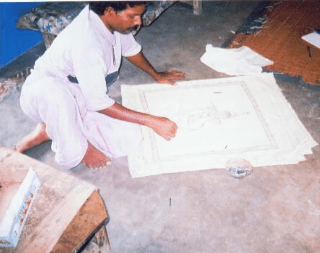

Once they are thoroughly dry, they are folded and pressed. Straight lines are drawn in charcoal along the creases formed. This defines the decorative panel within which the main theme will be drawn. The charcoal stick is held between the thumb and forefinger. The other fingers run along the creases, providing movement and support.

In outlining the main theme, the leading figures are sketched first, followed by the others. The charcoal drawing provides the basic layout. All details are subsequently filled in by pen.

A woolen blanket is spread on a wooden table. This provides a smooth work surface and also absorbs color seeping through to the reverse side. The myrobalan-processed cloth on which charcoal outlines have been made is placed on it. The iron mordant is kept in a mug.

The pointed kalamis used to make outline drawings and other line details. If larger areas in black are desired, the second pen with the broader tip is used.

The outline is drawn with charcoal and iron acetate.

The procedure followed is the same as for iron acetate. This operation has to be accomplished very skillfully so that there is no smudging of mordant. The fabric is then taken to the river. It is opened out and held in the flowing water by two persons holding either end.

There is no overlapping of fabric. It is kept in this position in the river for above five minutes. It is then lifted out, shaken thoroughly and dipped back into the water. By this time, the excess mordant would have been swept away in the flowing river.

The dipping and squeezing procedure is repeated two to three times. All the impurities are removed, and the unevenness in mordant painting is neutralized by these actions.

Prior to boiling, the fabric is opened out and inspected. If any spreading or blotching of iron or alum mordant is noticed, it is rectified by the application of the juice of raw lemon on the affected areas.

A large opened-mouthed copper vessel is filled with sufficient water to soak the required quantity of cloth. Copper would be preferable as there would be no admixture of metal to reduce the color. Pobbaku (Narigama alta )is mixed into the water by hand, and the water is brought to a boil.

Powdered Chevalakudi (Rubia Cordifolia linn) and Suruduchakka (Ventilago madraspatana gartan) are added. The mixture is stirred continuously.

It is moved in and out of the solution with a wooden stick until the entire quantity has been put in. The fabric is allowed to remain in the liquid until it boils over. The cloth is taken out, cooled with cold water, taken to the river and washed in the flowing water.

At Kalahasti, material with black filling is boiled separately from that with a dominant red color. After washing the cloth in the river, it is spread out on the wet sand of the riverbed for a few hours. At intervals water is sprinkled on it to keep it wet.

This is done twice. It is then wrung out and dried on the wet sand. If a second boiling in madder is not required, the cloth is put through the sheep dung bleaching stage.

If a deeper shade of red is required, the process of myrobalan and alum application, washing in the river for removal of excess alum, boiling in madder and washing and drying in the river is repeated for a second time.

For bleaching purposes either sheep dung or cow dung may be used. Sheep dung is more effective as it contains a higher proportion of sodium carbonate.

A handful of dung is mixed in enough water to bleach 10 meters of cloth. The mixture is kept in clay. The cloth is dipped in this solution, taken out, squeezed and kept aside. Fresh dung with water is added as required. The material is rolled up and kept through the night with the dung mixture.

The following morning it is taken to the river, beaten and washed in the flowing water. It is dried on the wet sand. To keep the cloth wet, water is sprinkled on it every few minutes. The fabric is exposed to the sun. This bleaching process continues for four to five days until the non-mordant portions become white.

After the bleaching process, the cloth is dipped in a milk solution. This helps in applying the color only to the areas required, that is, it prevents the running of one dye color into other dyed areas of color.

The yellow used may be the extract of either the myrobalan flower or pomegranate rind. It is applied with the round-tipped pen in the same way as in filling in the alum. After painting it yellow, the cloth is washed in the river as in the case of alum painting and dried on the sand in the same way.

Surruduchakka, which has a basic brown color, is used to darken the shade of red got from Pobbaku and Chevalikodi. The blue color is prepared with a solution of indigo mixed with a little alum. Blue is applied with a broad-tipped pen in the same manner as the alum.

Painting red on blue yields violet, painting yellow on blue provides green. After the application of blue, the cloth is washed in the river as after boiling for Manjishta (madder). The excess blue is washed away and all the dirt is removed.

Design Themes

As mentioned earlier, the themes adopted for the designs are from the Puranas or epics. These stories are depicted in the form of a series of horizontal panels with the script running through with the more important incidents receiving a larger layout.

At times the image of a particular god or goddess with the appropriate vahana (vehicle) is depicted. To a large extent colors are used symbolically; blue is associated with deities, red with demons, Hanuman is depicted in green and so on.

Yellow is used for female body color and also to simulate gold ornaments. Animals and geometrical designs are traced in black against a white background. The motifs used in the decorative borders are highly conventionalized. These include different forms of the lotus flower, the cart wheel, parrots, an interlacing pattern of leaves and flowers and the cat’s paw.

Markets

Historically, as described above, Kalamkari wall hangings have had a popular demand in diverse markets. Currently, Kalamkari paintings are sold through Lepakshi showrooms across the country, Cottage Industry and other craft stores. Exhibitions conducted by both the state and central governments (handicrafts) and others also provide a channel for sales and publicity regarding the craft.